The plan to make a giant hot water bottle underground

During the Cold War, Sweden stored 300,000 cubic metres of oil in caverns beneath the city of Västerås, in case of a war that could cut off their energy supplies. Recently, Swedish energy company Mälarenergi has decided to clean and repurpose the caverns as a large underground hot water tank that can hold up to 120 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

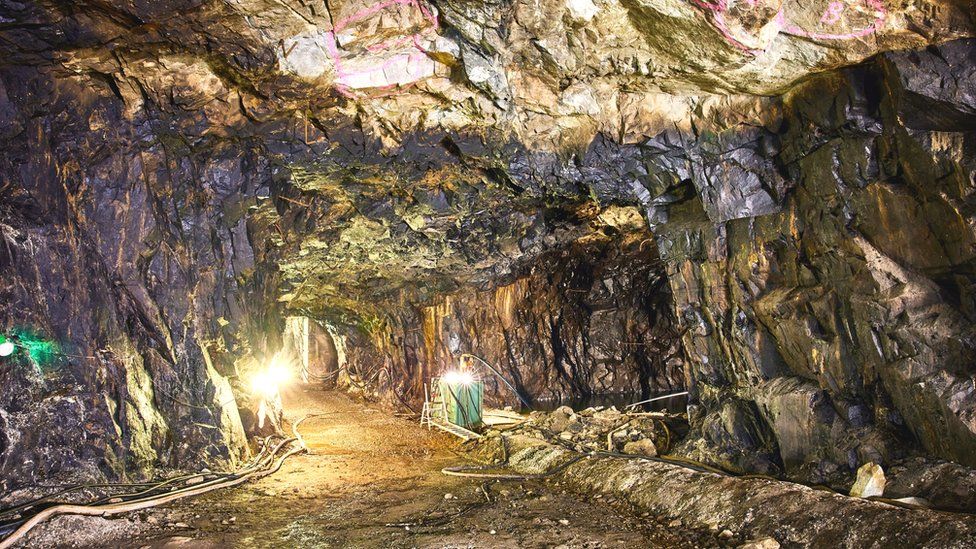

This project will create the largest underground thermos in Europe and will be filled with hot water reaching up to 95C. The location of the caverns remains undisclosed, but Lisa Granström, acting head of business unit heat and power, says that the caverns are warmer and damper than expected and still smell a bit oily. The new underground tank will be 11 times bigger than the largest above-ground hot water tank Mälarenergi currently has nearby.

Experts suggest that we should make more use of below-ground heat storage systems, like the one being developed by Mälarenergi in Västerås, as a means of caching warmth for later use. The heat from the underground hot water tank will be transmitted to a district heating network that provides heat to almost all households in the city.

The company plans to start filling the caverns with hot water by the end of the year, providing up to 500MW of district heating power. The heat comes from a nearby power plant that burns waste or biomass to generate electricity or thermal energy, but carbon capture technology is yet to be installed. The underground reservoir will help Mälarenergi maintain the heat supply to homes during peak demand in winter without reducing electricity production at the power plant.

Storing heat underground is effective due to the insulating properties of the ground, which makes it difficult for heat to escape. Mälarenergi’s caverns are expected to retain heat for several weeks, and the heat loss will be minimal once the adjacent ground temperature rises after a few years.

In London, the clay surrounding the tunnels on the Underground has been heated by people and trains, making it challenging to cool down tube carriages and platforms. The Västerås project is not the first of its kind, as a similar system in Finland supplies heat to 25,000 apartments all year round. Fleur Loveridge at the University of Leeds praises the cavern solutions as a great option among others for energy storage.

Picture Courtesy: Google/images are subject to copyright